Rockprodigy Revisited: An Interview with Mike Anderson

by Paul Nelson

In 2006, Mike Anderson– or as he was known on rockclimbing.com, “rockprodigy”– posted an article here called “The Making of a Rockprodigy,” which laid out some reasons to do specialized, periodized training as a means of improving in climbing. I remember reading the article, and getting psyched on actually using my time in a climbing gym not just to project the pink-tape boulder problem over and over again, but to get better in measurable, quantitative ways.

|

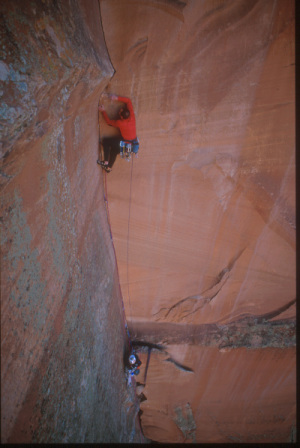

| The Lowe Route, 5.13 V, Zion National Park. Photo by Andrew Burr. |

His trad resume extends to granite as well: the FFA of Arcturus (5.13) on Yosemite’s Halfdome, and even a first-go team send of Free Rider (5.12+/13-) on El Cap, swinging leads with his twin brother Mark (Even to this day, an El Cap free route has not been onsighted or flashed. Mark and Mike do not claim this for their send, since Mark had previously aided a portion of the route, but it is significant that this is about as close to flashing an El Cap route as anyone has done yet).

A few years later, in 2009, I had moved from Castle Valley, Utah, to Ohio (don't ask), and received a message out of the blue from Mike. He had also just moved to the flatland hell of the Buckeye State from Colorado to work on a PhD as part of his job as a USAF engineer, and was looking for climbing partners who could also help his wife and him babysit their two young boys while climbing. I was more than happy to oblige.

This move to Dayton, Ohio, which was a couple hours from the Red River Gorge, signaled a move toward hard sport climbing for Mike. He also began further refining the training that he had original outlined in the rockclimbing.com article, and spent hours in gyms and on hangboards at his home, documenting his progress on spreadsheets, and waiting for the inevitable “peak” in his performance, which would hopefully coincide with the best fall conditions at the RRG in early November. Many locals at the RRG, myself included, would look at Mike like he was crazy, when he would explain, “No, I’m not climbing on this beautiful September day, because I have to hangboard tomorrow,” but the benefits of his training would always pay off a few months later, as he would make short work of steep Madness Cave routes.

|

| Mike on "Transworld Depravity" (5.14a), at the Red River Gorge's Madness Cave. Photo by Janelle Anderson. |

When we first met, I recall Mike glumly saying, “Yeah, my brother decided to climb 5.14, and I decided to have kids” (Mark has long been a slightly stronger sport climber, and Mike more of a trad climber). Only a few years later, however, his brother is now a father, and both of them climb 5.14. This really sums up what is so cool about both brothers’ climbing– they are operating at very high levels, but do so while maintaining jobs, families, and very little time on the rock compared to professional climbers.

Most of this comes down to their very efficient training program, which is intended to give “weekend warriors” the biggest bang for their buck so that they can improve and climb hard while still having houses, families, and 9-5's. The seeds of this “rockprodigy” program were sewn in the rockclimbing.com article, but it has now come to full fruition with Mike and Mark’s book The Rock Climber’s Training Manual: A Guide to Continuous Improvement, which is being hailed as one of the most comprehensive, definitive training books in the climbing world.

I got the opportunity to catch up and chat with Mike, who has since moved back to Colorado. We didn’t talk much about the specific details of training, but if you want to learn more, check out the article, and then consider getting the book.

Paul: Starting off, why should climbers do specialized training– hangboards, campus boards, structured routines on plastic– rather than just climb?

Mike: The main reason is that just climbing is not an intense enough activity to cause the type of adaptation that you need as a rock climber. Because climbing is such a complicated sport, a lot of times we are limited not by just finger strength on a given hold, but by a lot of other factors like endurance for a particular route, weather, technical movement, etc. We never really reach our true physical limit. If we want to develop our physical capabilities, we need to push our bodies to that physical limit. So, it’s helpful to do supplemental exercises that work on just the physical characteristics that you want to develop.

P: And at what point would you say that a very psyched, passionate, but new rock climber should start getting into this specialized training?

M: The standard dogma in the past was like, “well, you need to climb for a couple years before you get into specialized training.” I don’t really buy that. If you start out running, people would not tell you, “just run for a couple years,” and THEN you’ll be ready to train for a race. As a new climber, it’s really a spectrum. Your total time climbing should devote some time to technique, and some time to training. You obviously want to spend more time on technique and practice, but there’s still plenty of time to spend on physical training as well. You can make great gains as a beginner with very little time put into it, and it’s also possible to combine practice and training together, too, which we go into in our book. But, you’ll find as you progress as a climber you are eventually going to need to put more time into training in order to improve. All climbers hit a plateau at some point, and at that point they should consider starting a deliberate training program, rather than just haphazardly going to the gym.

P: Taking off from your point about devoting set times to technique, physical training, and although you didn’t mention it, even Warrior’s Way-styled mental training, it struck me in reading your book how we all tend to see these different aspects of climbing as very separate from one another, perhaps too much. And they’re not separate. My friend Curt Shannon quips, “the key to great footwork is really strong fingers.” It’s humorous, but there is truth to that. Good technique and good headspace comes when the climbing feels easier to you, and if you train, those holds and moves will feel easier.

M: Right, that was a huge revelation that my brother had. When he began training, it was not so much that he was able to climb harder routes, but that the routes he was doing started getting more enjoyable. He used to always climb in a way that he felt sketched all the time; he was motivated to tick really hard routes, so he would suffer through them, but once he started training, he realized that the actual climbing was fun! Maybe you don’t aspire to climb 5.13, but a bit of extra finger strength and endurance will make 5.10s feel smoother and less sketchy as you struggle to place that cam or whatever.

P: Totally! I still remember the first hard climb I ever did, where I was able to stop in the middle of the crux and realize that I was having a great time, and enjoying the actual moment, rather than being miserable and only enjoying it after I lowered to the ground to revel in the send. It turned Type II fun into Type I fun.

Anyway, going off of your comments about your brother Mark, with whom you wrote this book, could you tell us what some of the contrasts in how you guys approach climbing are? Do you guys have different goals in climbing?

M: Well, for my goals, I used to do much more trad and big wall climbing, and I feel that those styles of climbing require much more technique, so I structured my training in a way that allowed me to spend more time outside. The techniques you need for crack climbing are pretty specialized, so I was just trying to get more practice on real rock. And that’s a trade-off that we hear about a lot– I might get an email from someone in Bishop who wants to train, but also wants to climb outside a bunch. And this is possible, but it’s just less time-effective. It takes more time to get a thorough workout outside than it does on a hangboard; you can trash yourself in 90 minutes on a hangboard, whereas 8 hours outside might not do that.

But anyway, it’s been seven or eight years since I was doing all that big wall stuff, and in that time, I had a couple kids, moved to the East, and shifted my focus more to sport climbing. And for a sport climbing focus, the ability to do crux moves has always been a limiting factor for me. I don’t feel like I have any kind of natural talent for hanging on really small holds; that’s something I have to work on. There are other climbers who, within six months of climbing can squeeze on really small holds, so for them they need to see what their own weaknesses are and work on them. But for me to progress through the grades, I’ve had to really focus on power, which is what my brother was doing years ago, since he was always more focused on sport climbing.

I’ve always been limited by the moves, not the ability to link the moves, so I really need to improve my ability to do single hard moves, so I need more finger strength. And to improve that, I’ve found that I just have to stick to the specialized training; focus more on hangboards than climbing outside all the time. But I still get out occasionally; this season I just started a hangboard workout, but am going to Moab for Thanksgiving. I’m going to miss a hangboard workout, so I’m going to try to get out to Indian Creek for some sort of workout, get out on the rock and have some fun. Or maybe somewhere else for a good workout, like to Mill Creek or Big Bend.

P: Haha, yeah, Indian Creek is not the best substitute for a hangboard workout.

M: No, but still, missing one out of nine workouts isn’t going to kill you.

P: So, when I first met you, you had just moved to Dayton, Ohio to start a PhD program, a few hours from the Red River Gorge. How much did this non-climbing life change affect your climbing? Do you think you would have jumped into sport climbing as aggressively if you had not had to move East for your profession?

M: It’s hard to say. I always knew, consciously, when I was doing the big wall stuff, that I was sacrificing top end sport climbing performance. It’s possible to be great as both if you’re a full time climber, but if you have other things in your life, you have to pick and choose if you want to be the best you can be at something. And I still sport climbed at a pretty good level even when I was doing more trad stuff.

But did I feel like I was making a choice? I don’t even know if I would have stuck to the big wall stuff even if I had stayed in Colorado. I felt like at the time that was a great time to be in the big wall free climbing mode; in Zion it kind of felt like a golden age, that there was a lot of opportunity and I wanted to do FAs while they were still available.

P: Have you had any desire since you moved back out West to get back into big wall free climbing?

M: Absolutely, in a theoretical sense! I sometimes think I don’t have the tolerance or character for a lot of the work anymore. I tried to talk my brother into doing some bigger stuff this summer, but it didn’t work out. But I certainly still have ambitions for that.

P: You’re just not doing the drive to Zion from Colorado Springs every weekend anymore (Mike used to regularly drive from Colorado to Zion for a weekend, 11 hours each way)?

M: No, I have not yet been back to Zion since I moved back.

P: Ok, so one more question about the whole brother thing. You guys are identical twins; I know that researchers in the sciences love using twins for various experiments about nature vs. nurture, since they have the same genetics. You and your brother are both very analytical, research-driven engineers. Did the fact that you guys are twins play into your training research, say, in comparing each other’s progress with hangboarding or anything like that?

M: Absolutely, and that’s been a huge advantage for us. For example, you follow similar training to what I do, but I would be skeptical of drawing conclusions in comparing my data to yours because we have such different genetics. However, because Mark and I have such similar makeup, we can feel pretty confident drawing conclusions from the data of our training programs, or contrasting them.

|

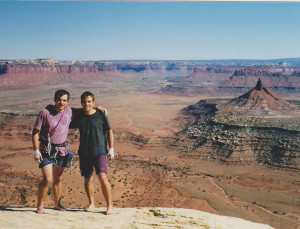

| Mark and Mike waaaaay back in the late 1990s, on top of North Sixshooter, Indian Creek, UT. |

P: So, a question about the age issue. You’re 37, approaching late 30s and 40s. Have you felt any signs of age catching up with you in your climbing?

M: Well, about when I turned 30, I started noticing some changes, but since then it’s more or less flatlined. The biggest thing with age is your ability to recover, and it also might get a bit more difficult to improve with training as quickly (though that could be age or just because your body gets desensitized to training). I felt those challenges when I was in my early 30s, but not much more. I still feel like I have the same potential that I did in my early 30s, and it really all comes down to how much effort I am able to put into my training and performance, not my age.

And in a lot of sports, not just climbing, the general wisdom has been that the younger you are, the more powerful you’ll be, and the older you are, the more endurance you’ll have. But I feel like in climbing, technique is so important, and we develop it over a lifetime, so the older you get the better form you have. At least for me, I hope to be climbing hard into my sixties, barring some bit injury.

P: Speaking of injury, your book had a great chapter on injury prevention and rehab for overuse injuries, but I noticed that you didn’t say much about catastrophic injuries. I know when I first met you, you were just coming off of a broken back, and two years ago I was on crutches for six months after fracturing a foot. So, what would you say to someone who suffers one of these injuries? Take time off, train other parts of your body?

M: That’s a good question; it never occurred to us to put that in the book, and that whole subject can be very personal. This is one of those instances in which I differ from Mark; I really like to have more balance between climbing and the rest of my life. For me, I took my broken back as an opportunity to take time off from climbing. Training the wrong way could have brought about some bad spinal issues, and even though I probably could have done some hangboarding, I kind of stepped back and re-evaluated my priorities. In sport climbing I had plateaued a bit, and I had just started a PhD program, so it was really good to just take a break.

But that said, a lot of times, especially for lower body injuries, there are a lot of things you can do to keep in shape while recovering: core, hangboarding and even campusing.

P: Yeah, that was definitely beneficial to my foot injury, I did two hangboard cycles and actually came out of the injury stronger in my upper body and fingers than when I had gone into it.

Anyway, final question– the nickname “Rockprodigy.” “Prodigies” are people who excel at something very quickly and naturally– Mozart writing concertos before he was 10, Picasso reaching the limits of realism by the time he was a teenager, that sort of thing. But in reading and hearing about your evolution as a climber, you were not really a prodigy. You put your time in, working through the grades at Smith Rock. It’s not like you were Dave Graham, climbing 5.13 in your first year or anything. So what’s up with the name?

M: Ok, great question! The name came up on a whim, when I had to have a username to sign up for rockclimbing.com back in the early 2000s. I was really into this band, Tenacious D, at the time, and they had this awesome song where they say, “there’s no such thing as a rock prodigy, because rock’n’roll is bogus."

|

| Tenacious D could DEFINITELY benefit from the Anderson brothers' training program. |

It was all a joke, but because the internet has no sense of humor or sarcasm, people took it as this arrogant, grandiose title, when I was just quoting my favorite band.

P: Okay, so THAT’S why, in the past, when I’ve googled your article, sometimes Tenacious D lyrics come up.

M:Yup, not a lot of people got the reference. It was all tongue-in-cheek, and I’m not claiming to be some rock star, but as the article got recognition, the name started getting some “street cred,” so we decided to keep using the name for our training program and even the hangboard that we designed for Trango.

P: And you’re not having to pay royalties from your hangboard sales to Tenacious D?

Hmm, let’s not mention that. We’re hoping that eventually, some REAL prodigy will use our hangboard and just fulfill the name. And I’ve still got two young science experiments I’m working on now, so we’ll see.