Know Your Land, Pt. 1: Climbing on Federal Lands

by Paul Nelson

Every once in a while, my facebook newsfeed shows up some photos of friends climbing on beautiful Kentucky Sandstone. I know exactly where this is, of course– it’s the Red River Gorge! But then I notice a recurring pet peeve. For some reason, there is an “area” on facebook that many people tag photos, or check themselves in, which is called “Red River Gorge National Park.” That sounds okay, right? Except for one problem; there is no Red River Gorge National Park.

You may think, “So what? You’re just arguing semantics here.” However, given the complex nature of land management and climbing regulations at the Red, as well as the larger issue that who manages the land that we climb on can often dictate how we can climb on it, it is a good idea for climbers to have some basic knowledge of which areas are public, which are private; which are for-profit, which are not; Wilderness (with a capital “W”) or frontcountry; national or state parks.

Many climbers may bristle at bringing up this topic. The senses of adventure and independence that draw many of us to climbing do not like to think about management, rules, and The Man telling us what we can and can’t do. We like to think of climbing areas, even those that are manicured and developed, as frontiers of discovery and ourselves as explorers.

|

| Follow the rules, deadbeat! |

However, ignorance is not bliss. To go back to the example of the Red River Gorge, the area that many people assume is within “Red River Gorge National Park” might be National Forest where no new bolted routes are allowed, or a private preserve where no runouts or "victory whips" are allowed. It might be a climbing coalition-owned preserve where almost all rules are climber-friendly, or a State Park with no climbing whatsoever allowed. Land ownership is complicated and we need to know the distinctions. About the only kind of land ownership that is NOT at the Red is National Park!

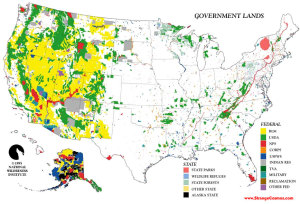

These articles will briefly go through some of the histories and philosophies of many public lands in the lower 48 (whether national, state, or municipal-owned), as well as touch upon some of the complexities that arise when there is more of a jumble between public and private, profit and non-profit, a phenomenon that is more common in the densely-populated eastern U.S. Part I here will focus on federal lands (I don't like to say federally "owned," because they are in fact owned by ALL Americans). Part II will look at state-owned climbing areas. Part III will look at the various types of private lands that contain climbing.

Regardless of who owns what land, however, be aware that there are rarely any standard rules that run across all lands of the same type. Yosemite and Canyonlands are both National Parks, but one allows new routes with fixed anchors, and another does not. Hueco Tanks and Enchanted Rock are both state parks within Texas, but only one has entire areas closed off, requires reservations and tour guides.

Before we go into the details of each type of land ownership and how they relate to climbing, here are a few broad facts: we will always be either climbing on private or public land. Public land can be federally, state, or city-owned under various types of agencies. Private land can range from “the landowner says I can climb here” to for-profit climbing parks. To complicate things further, there is also a middle ground between public and private, in which non-profit, often-untaxed entities purchase land and give access to the public.

Although there are exceptions, in general the western U.S. has many more federally-owned public climbing areas, while the East has more on private land. The reasons for this are complex, but for the most part it comes down to the fact that the federal government claimed huge amounts of western land after the Civil War, at a time when formal or informal private ownership was already established through most of the East. In the case of climbing, many of the cliffs that we know and love happened to be naturally beautiful places that would eventually become either state or national parks. Or even if they were not perceived as beautiful, they may have been in areas too remote for agricultural or urban development, and thus became national forests or Bureau of Land Management lands.

|

| Federally-owned lands in the US |

NATIONAL PARKLANDS:

Americans are proud of their national parks; the very idea of a park owned by a nation for the use of all its citizens, rather than a select few aristocrats, originated in the United States with places like Yosemite, Yellowstone, and even Hot Springs, Arkansas (seriously). Today, the most famous national parks protect “natural” landscapes like the Grand Canyon, Everglades, Death Valley, and climbing destinations like Yosemite, Zion, and Joshua Tree, but national parks also include more urban, manmade sites such as the Statue of Liberty and monuments in Washington D.C.

|

| Yes, it's technically a national park. No, that doesn't mean you can climb it. |

In addition to national parks, the National Park Service (NPS), which is part of the US Department of the Interior, also manages national monuments. These are usually (but not always) smaller than national parks, can be more focused on historical or archaeological sites, and are designated by presidential decree rather than an act of Congress. Often, national monuments later become parks, such as in the case of Zion, Arches, and more recently Joshua Tree. National reserves such as City of Rocks, national recreation areas such as Glen Canyon and the Sawtooth Mountains, and Wild and Scenic Rivers such as the New River Gorge and the Obed are also managed by the NPS. All areas managed by the NPS are referred to as “National Park Lands.”

The founding 1916 philosophy of the NPS had two goals:

- To “conserve the scenery and the natural and historic objects,” and to

- “provide for the enjoyment of the same” and “leave them unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations.”

Obviously, these can often conflict with each other: if you 100% conserve the park, no human visitors would be allowed, if you 100% provide for visitors, then the park will be overrun and lose its natural qualities. Each national park has its own approach to these goals, as anyone who has visited a crowded Yosemite Valley or Zion Canyon can attest. And the “leave unimpaired” for future generations thing is even tougher. Parks of the early 1900s did not have problems killing predators, encouraging visitors to feed animals, or building huge luxury lodges within their boundaries, which most of us today would be opposed to. And we have no idea what practices we do in today’s parks might seem detrimental to future generations. Personal drones were just banned in national parks; we're not sure how this will look in the future!

Philosophical debate aside, all of this has some interesting implications for climbing in terms of the safety of climbers, their impact on natural resources, and their impact on other visitors. Most national parks are fine with dispersed trad climbing (especially in Wilderness Areas, more on those later).

However, even for remote trad climbs, some parks still prohibit routes on distinctive formations (such as Dean Potter’s controversial solo of Delicate Arch in Arches, a feature that appears on Utah's license plates). Others are hostile to permanent anchors– no new bolts are allowed in places like Canyonlands and Capitol Reef, and no bolts at all are allowed in Grand Canyon. Still others, such as the New River Gorge, require lengthy bureaucratic processes to put new bolted routes up. Mesa Verde allows no climbing at all, due to its historic nature. And, for some reason, there is a blanket ban on BASE jumping in all NPS lands.

Bouldering is all-out banned in very few national parks, though it is in some monuments and historic sites. However, most parks do forbid bouldering along popular hiking trails, on distinctive formations, and might not be cool with the use of chalk defacing the rock.

Sport climbing is without a doubt the most likely type of climbing to be prohibited in national parks. While many parks like Joshua Tree, Rocky Mountain, and Yosemite have sport routes, none really have concentrated, easily accessed sport areas like Rifle or Smith Rock– their sport routes tend to be more remote, dispersed, and even more minimally bolted. Other NPS lands such as City of Rocks and the New or Obed river gorges have much more concentrated sport crags that were developed before rules were put into place, but even these areas have largely restricted new route development. You are probably not going to find your next mega sport crag in a national park.

The biggest thing to keep in mind on national parklands is that these are the most critical areas to “Leave No Trace,” though this may seem silly in areas that are overrun by tourists, have graveled trails, and tons of interpretive signs. For the most part, the longer climbing has been prevalent in the park, the friendlier managers will be to it (Yosemite climbing definitely gets a lot of “free passes” for its historical significance, despite what irate climbers will tell you). But regardless, minimal impact is a good idea everywhere. Keep in mind that national parks exist so that people can visit them. For every hiker who marvels at how cool you are for climbing, there is someone else who is offended at chalk marks, bolts, or fixed ropes ruining their “natural” experience. Try to be dispersed, stay away from popular, crowded areas, and check the specific regulations of each park if you’re thinking about doing new routes.

SPECIFIC NATIONAL PARKLANDS KNOWN FOR CLIMBING:

- Acadia National Park, ME

- Arches National Park, UT

- Black Canyon of the Gunnison National Park, CO

- City of Rocks National Reserve, ID

- Devil’s Tower National Monument, WY

- Canyonlands National Park, UT

- Colorado National Monument, CO

- Grand Teton National Park, WY

- Great Falls National Park, DC, VA, MD

- Joshua Tree National Park, CA

- King’s Canyon, CA

- Mount Rainier National Park, WA

- Mount Rushmore National Memorial, SD

- New River Gorge National Wild and Scenic River, WV

- North Cascades, WA

- Obed National Wild and Scenic River, TN

- Rocky Mountain National Park, CO

- Sawtooth National Recreation Area, ID

- Shenandoah National Park (Old Rag), VA

- Yosemite National Park, CA

- Zion National Park, UT

NATIONAL FORESTS:

The history behind the creation of national forests is interesting, and followed a bit of a different trajectory than national parks. Around the last third of the 1800s, when the US government was designating large, wild national parks in Yellowstone, Yosemite, and Sequoia, some foresters such as Gifford Pinchot became concerned that forested public lands in both the East and West would be vulnerable to clearcut logging, and urged protection of them as well. But here’s the thing: the initial goal of the United States Forest Service (USFS) was less national park-style preservation of resources for the benefit of visitors, but for conservation. They intended to allow logging, ranching, and mining within national forests, but believed that it should be tightly regulated at the federal level. For this reason, the USFS is not a part of the Department of the Interior like the NPS is, but of the Department of Agriculture. Yes, the guys who inspect grain and livestock are also the ones who control your access to nice summertime climbing.

Very quickly after the initial Forest Reserve Act of 1891, land managers realized that Americans enjoyed recreation on national forests: hunting, fishing, and later hiking, climbing, skiing, boating, and mountain biking. Enjoyment of national forests became just as important an objective as extractive exploitation in management. Probably stemming from this philosophy, USFS lands have long been slightly more friendly to unhindered climbing than NPS lands. Climbing areas in national forests might not be quite as scenic or huge as a lot of national parks, but they often can be more accessible, with more bolts and user-friendly rules. Trad cragging at Index, WA, Lover’s Leap, CA or Paradise Forks, AZ; concentrated sport cragging at Maple Canyon, UT or Clear Creek, CO; bouldering at Joe’s Valley, UT or Rocktown, GA; these are all great national forest areas with long histories of climbing.

|

| Lover's Leap, California. Trees and granite in a national forest. |

That said, when areas get crowded by both climbers or other recreationists, the rules can descend. User fees are becoming more and more prevalent, especially in highly populated areas of Colorado and California. Endangered species such as primroses in Logan Canyon, UT can cause whole crags to be closed. Archaeological and crowding concerns have also effectively ended all new bolting in the portions of the Red River Gorge that are public national forest. And, most tragically from many climber’s perspectives, sometimes national forest lands are vulnerable to extractive industries, as the ongoing and tense conflict between climbers at Oak Flat, AZ and a foreign-owned copper mine shows.

That said, cliffs on national forests for the most part can be more accessible and open to development than they are in national parks, as those of us who are lucky enough to live near climbing on national forests, both in the East and West know.

SOME CLIMBING AREAS ON NATIONAL FOREST LANDS

- American Fork, UT

- Boulder Canyon, CO

- Clear Creek Canyon, CO

- Cochise Stronghold, AZ

- Independence Pass, CO

- Lake Tahoe area crags, CA

- Little and Big Cottonwood Canyons, UT

- Logan Canyon, UT

- Looking Glass Rock, NC

- Maple Canyon, UT

- Needles, CA

- Ten Sleep, WY

- Red River Gorge, Southern Region, KY

- Rocktown, GA

- Sam’s Throne, AR

- Seneca Rocks, WV

- Wild Iris, WY

- Vedauwoo, WY

BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT:

So, what about those huge tracts of public land that are not forested, and not national parks? There are still millions of acres like this, which in 1946 were grouped under the Bureau of Land Management (BLM). All BLM lands are in the western US– in the East, unforested lands have all long been either farm or city lands. Although not under the Department of Agriculture like the USFS, the BLM also caters heavily to extractive industries (an environmentalist friend of mine refers to it as the “Bureau of Livestock and Mining”).

|

| A typical representation of BLM land. |

|

| Another typical representation of BLM land. |

For the most part, BLM lands have been the most “hands off” in terms of usage; in a lot of places this is where you can camp for free, drive your 4x4 right up to the crag, and put up routes however you want. Moab, Utah, is even a Mecca for BASE jumpers, because it has some of the largest cliffs outside of the national parks that ban the practice. But, as with parks and forests, increased usage means more rules and regulations. Some climbing is in specific fee areas; other places like Indian Creek, UT are on the verge of shutting down free camping. The BLM has even started managing some areas that for all intents and purposes are national parks, such as Grand Staircase-Escalante, UT (which is not particularly supportive of climnbing), and Red Rocks, NV (which has TONS of climbing).

BUREAU OF LAND MANAGEMENT CLIMBING AREAS:

- Bishop, CA

- Castle Valley, UT/a>

- Homestead, AZ/a>

- Indian Creek, UT/a>

- Red Rocks Canyons National Conservation Area/a>, NV

- San Rafael Swell/a>, UT

- Trout Creek, OR

- Virgin River Gorge/a>, AZ

- West Desert, UT (Ibex, Notch Peak, etc.)

There are a few other random federal agencies that happen to manage land with climbing on it. The US Fish and Wildlife Service's preserves include the scattered granite of Oklahoma's Wichita Mountains, and Washington's Frenchman's Coulee. And the Corps of Engineers manages some reservoirs that have cliffs on their shores, such as Lake Summersville, just north of the New River Gorge.

And then there is the special case of federal Wilderness Areas. These are specially designated areas within national parks, forests, or BLM lands that somehow have remained roadless and undeveloped. Whereas national forests originated in the idea of responsibly conserving resources, and parks in the idea of giving citizens great outdoor vistas to visit, Wildernesses are intended to be preserves of how land would be with no human presence at all; recreation is possible in them, but only with very light impact.

At least that is the theory, going back to the 1964 Wilderness Act, which realized that even parks and forests were becoming very developed and accessible. True, Wilderness Areas are not completely untrammeled– they still have trails, some fire rings, and the occasional sign. Sometimes, Wildernesses have even been designated in areas where primitive roads or wagon trails once were, but are now overgrown. And, even the idea of preserving a completely non-human landscape may seem a bit silly when we consider that Indians used most land in America intensely before colonization.

Regardless, here are the rules for Wilderness Areas, like them or not: no "mechanized" travel; this excludes not only cars, 4x4s, and dirtbikes, but also mountain bikes, but still allows horses. No permanent structures are allowed. Even chainsaws and helicopters are forbidden except in cases of extreme emergency.

But what about climbing? In theory, Wilderness Areas do not allow any fixed gear (bolts, pitons, webbing) whatsoever, since it is tantamount to littering. But in reality, climbing routes in wild areas tend to have fixed gear, just a little less of it, making long routes much more committing.

|

| Wind River Mountains, Wyoming |

Also forbidden are power drills, led to a controversial mixup, in which several years ago climbers claimed to have misread a map and established a heavily bolted route in a Washington wilderness area. In the Red River Gorge, the popular Funk Rock City crag was developed into several dozen excellent sport routes before it was designated wilderness, and a few exemplary volunteers wound up carrying out a much-needed rebolting several years ago entirely by use of hand drills (we're talking hundreds of hours of work here).

So, Wilderness Areas can seem to have silly rules, but think of them as just part of preserving the adventure of climbing in beautiful, remote areas. For this reason, even climbing areas within wildernesses may be very unpublicized, especially in comparison to more accessible crags. Be aware of the differences between backcountry wilderness and frontcountry crags that can exist within the very same national parks, forests, or BLM lands.

NOTABLE WILDERNESS CLIMBING AREAS:

- Clifty Wilderness (USFS), Red River Gorge, KY

- High Sierras, (USFS), CA

- Indian Peaks Wilderness (USFS), CO

- Linville Gorge (USFS), NC

- Lone Peak Cirque (USFS), UT

- Sawtooth Mountains (NPS), ID

- Vermillion Cliffs (BLM)<, AZ

- Wind River Mountains (USFS), WY

Click here for the next installment of this series, dealing with state and locally-owned climbing areas.

2 Comments

Add a Comment

Add a Comment

|

munky 2014-12-19 |

The Libertarian in me wants to say fawk it and go do what I please on my land. This is Merica', the land of the bald eagle, home to the savages, and free from government intervention gawd damnit!!! I have inalienable rights to do what I please on mah land! If i want to run around naked driving my quad while ripping bong hits and occasionally unloading my M-14 through the sweet desert architecture, by God-given right I will!!! |

|

PaulHutton 2015-02-24 |

Here Here! |

Previous

Previous